Wisteria – A Rare Dichroic Glass

Jul 17, 2025

Issue 3754

Did any of our readers see the Wisteria glass pieces that came up for auction recently? One lot had a set of Carder Steuben Wisteria tableware pieces grouped together in a set with Moser Alexandrit goblets. They were surprisingly very similar.

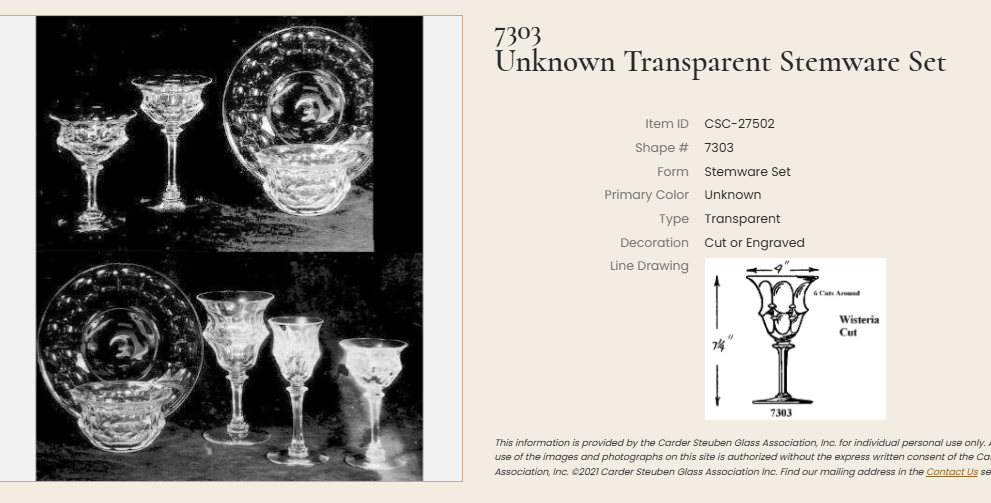

All the pieces in the grouping are Carder Steuben except the wine stems on the right which are Moser. Here is the set shown in the shape gallery.

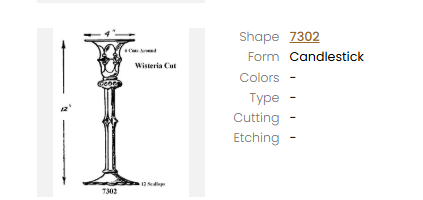

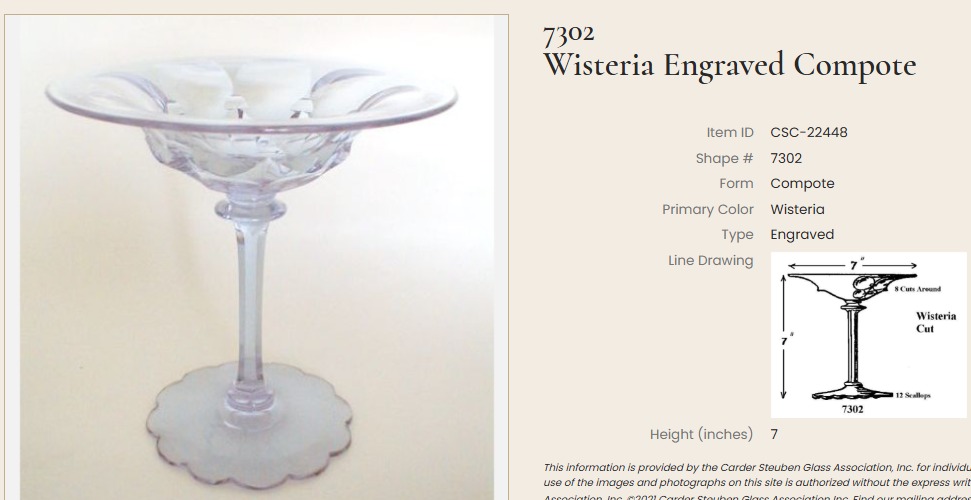

Other lots in the auction included a pair of Shape #7302 candlesticks and a Shape #7304 compote.

Thomas Dimitroff’s book Frederick Carder and Steuben Glass contains a wealth of insightful information about Wisteria glass. A review of the line drawings reveals a significant number of cut and/or engraved designs on stemware, bowls, centerpieces, and candlesticks—mostly within the 6000 to 7000 series of shape numbers. Wisteria, Carder’s dichroic blue-to-lavender glass that mimicked the gemstone alexandrite, is typically shown with cut decoration. These decorations range from fairly traditional patterns such as diamonds and fans to more streamlined designs featuring large facets.

Wisteria was a difficult color to produce, and very little of it has survived. Since it is referred to as “new” in a 1931 memo, it was likely only in production for a short time. On page 73 of Tom Dimitroff’s book there is a cost-per-pound chart organized by glass formula. Wisteria was the second most expensive formula listed, priced at $0.493 per pound—second only to Amethyst Ruby, which was priced at $0.571 per pound. This is probably because the mineral responsible for creating the color was the newly discovered rare earth element neodymium.

At last year’s Symposium, Amy Hughes of CMoG shared the dynamic history of chemistry and color in a beautiful and informative presentation about rare earth metals in glass. Rare earth elements are metallic elements found in nature and are used in many modern technical applications like cell phones, electric vehicles, and flat screen TVs. When applied in the correct ratios to a glass formula, they can also imbue a rainbow of colors, including some that change color under different light sources. Amy’s research credited Moser Glassworks with creating the first colored glasses using the newly purified rare earth elements in the mid-1920’s. Leo Moser’s experimentation led to the discovery of how to produce glass with “mystical” color-changing properties depending on the lighting source. For example, Alexandrit is purple in daylight but appears light blue under artificial light, while Heliolit transforms from sandy yellow to olive green. While Moser was the first to register trademarks in this new colored glass, other makers were also developing their own lines. Frederick Carder created his Wisteria glass that has the same color changing property as Moser’s Alexandrit glass.

REGISTRATION IS OPEN

The 2025 Carder Steuben Glass Association Symposium and the Frederick Carder Birthday Dinner are now open for registration!

The annual Carder Steuben Glass Association Symposium will take place September 19-20, 2025 at the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York. Plus, the CSGA is hosting The Carder Birthday Dinner, an event which hasn’t been held in several years. This dinner will be held on Thursday, September 18, 2025, at the Corning Country Club. You can register for both of these events on the CSGA website here.