CMoG Curators Deliver Two Informative Presentations

Oct 30, 2024

Issue 3727

We had the pleasure of learning from CMoG’s Amy Hughes and Amy McHugh at this year’s Symposium.

KINETIC COLORS FOR MODERN TIMES

Amy Hughes shared the dynamic history of chemistry and color in a beautiful and informative presentation about rare earth metals in glass. Rare earth elements are metallic elements found in nature and are used in many modern technical applications like cell phones, electric vehicles, and flat screen TVs. When applied in the correct ratios to a glass formula, they can also imbue a rainbow of colors, including some that change color under different light sources.

The 1800s saw significant scientific focus on the discovery of new elements. The compound Didymium was discovered in 1841, and in 1885 scientists successfully separated Didymium into its two component elements: Praseodymium (green) and Neodymium (purple-blue). It took over two decades before this scientific discovery was successfully incorporated into the production of glass.

Colored glass only began to gain interest in the late 19th century, keeping with the changing ideals of the time. Prior to that period, the focus of glassmakers was to create sparkling crystal-clear glass enhanced with applied engraved decorations and cutting.

Moser Glassworks is credited with creating the first colored glasses using the newly purified rare earth elements in the mid-1920’s. Leo Moser’s experimentation led to the discovery of how to produce glass with “mystical” color-changing properties depending on the lighting source. For example, Alexandrit is purple in daylight but appears light blue under artificial light, while Heliolit transforms from sandy yellow to olive green. While Moser was the first to register trademarks in this new colored glass, other makers were also developing their own lines. Frederick Carder created his Wisteria glass that has the same color changing property as Moser’s Alexandrit glass.

Moser still produces glass today, including glasses in some of the same colors that had first been created a century ago. Moser’s rare earth glasses stand as hallmarks of the successful combination of science, art, and design.

A RAINBOW OF COLORS

CMOG’s Curator of Modern Glass, Amy McHugh, gave a presentation surveying changing tastes, values and interests that occurred in the 1910s and 1920s, as reflected in the manufacture and marketing of decorative glass in general and tableware in particular. She showed an array of articles, clippings and advertisements—many in color—from trade publications, home décor magazines and newspapers of the times. It was interesting to contemplate the effect of these ads and articles on the home decorators and housewives of the era.

The late 1800s saw the beginning of a color revolution. Color began to impact all aspects of décor. Utilizing the technological advances occurring in the industry, glass manufacturers were producing new forms and colors in objects in Art Nouveau style, showing them next to largely colorless cut and engraved examples still in production.

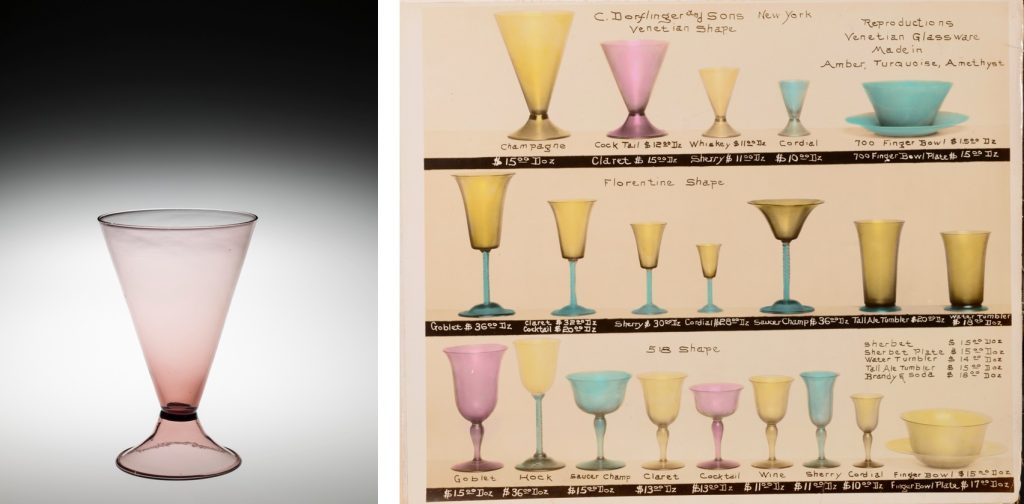

World War I, however, saw a decrease in glass production overall in the U.S. Dorflinger, for example, experienced a shortage of potash. The supply of synthetic dyes dried up, since most of it came from Germany. Companies had to shift to making other products, often utilitarian. Dorflinger coped with the potash shortage by bringing out a new line in 1915 labeled “Reproduction“—pastel colored glass inspired by Venetian designs—a contrast with the brilliant cut and engraved glass for which they were known. The new line proved to be a success with the public but nonetheless was discontinued in 1918 around the end of the war. Sadly, Dorflinger closed its doors in 1921. Postwar saw a nationalistic trend and a desire for “made in America” items with simplified designs.

Frederick Carder and Steuben Glass fit well with the new trend, having begun production of colored glass in 1904. It was featured in trade publications and newspaper write-ups. Steuben placed color ads in home décor magazines promoting their modern designs “in cool colors and quaint contours.” Then, in 1924, the H. Northwood Company published “The Lure of the Rainbow,” a pamphlet describing its radiant colored glassware. Despite the innovative color palette and a seemingly endless array of beautiful glass forms, Steuben sales began to decline. The production of a color catalog, color booklet and more colored ads in national publications failed to have a significant impact. In the 1930s, Steuben management made the decision to move to colorless glass.

BE AN EARLY BIRD

Our membership drive officially kicks off at the beginning of November, but we’d love it if you beat the rush and renewed your membership in the CSGA today! The dues of $35 for one person, or $55 for a two-person household will keep you as active members through December 31, 2025. It’s easy to renew online by visiting the CSGA website here. Thank you!